[This post contains spoilers.]

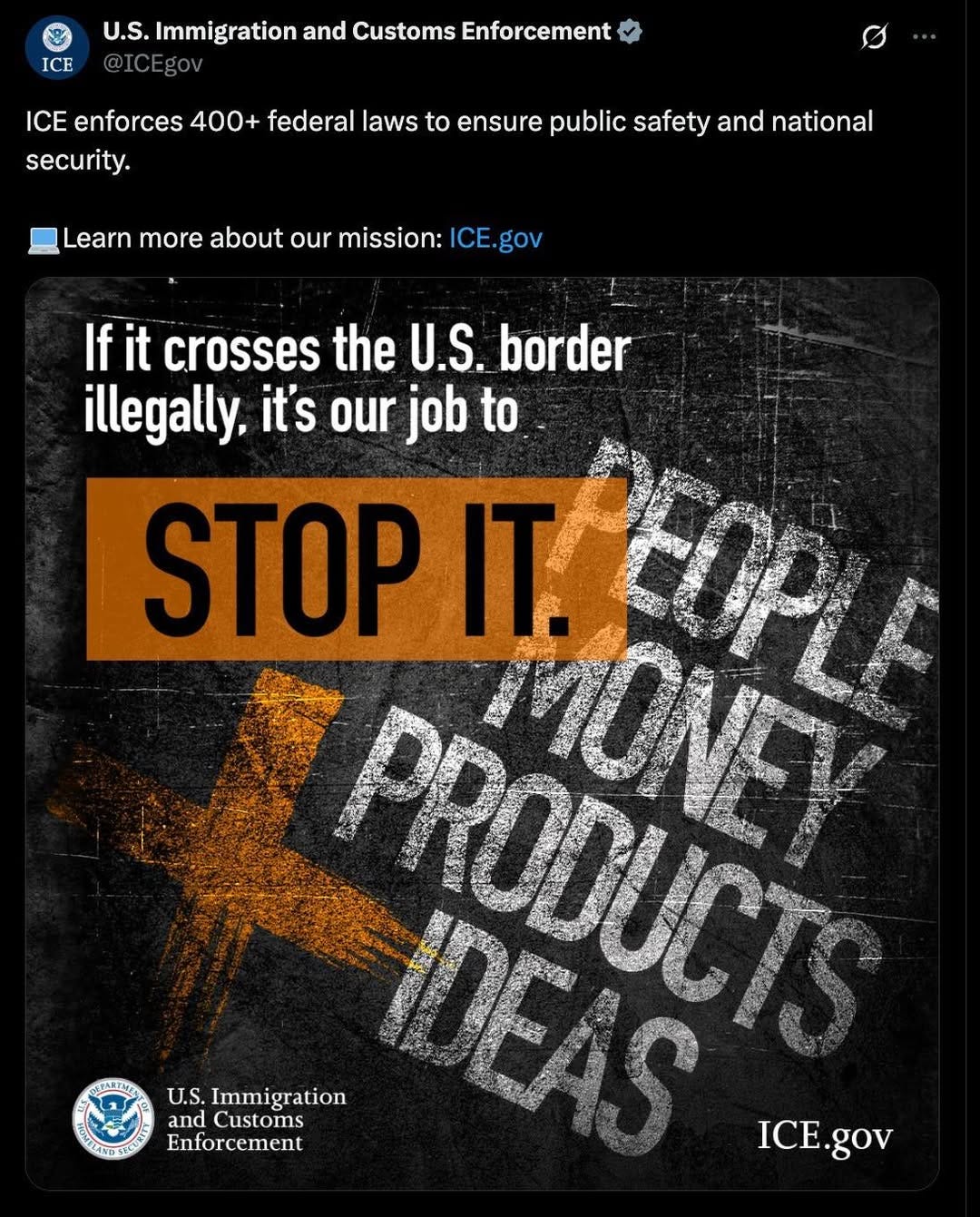

Sadly we have some reason to fear living under authoritarianism in the United States. According to Reuters (April 8th), Elon’s team at DOGE has been using AI to surveil government employees for perceived disloyalty. According to the BBC and many other sources, an innocent man has been sent without due process to a prison known for torture in El Salvador. President Trump has floated the idea of also sending American citizens to this foreign gulag, which is both horrifying and unconstitutional. And ICE is saying on their official page that they are going to stop anything which crosses the U.S. border illegally, “people, money, products, and ideas.” Ideas? What exactly is an illegal ideal? Most who voted for Trump, I assume, did not vote for sending American criminals to foreign gulags or for making ideas illegal.

.

In light of these unfortunate circumstances, now is a good time to watch, “The Lives of Others” (2006). The movie set in East Berlin in 1984 will remind you of obvious things, like living in a dictatorship is bad. It also will remind you that staying embodied and connected to others and the world around you, when the news cycle makes you want to numb out and be depressed, is itself an act of revolt.

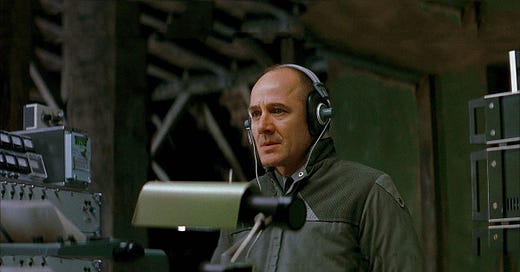

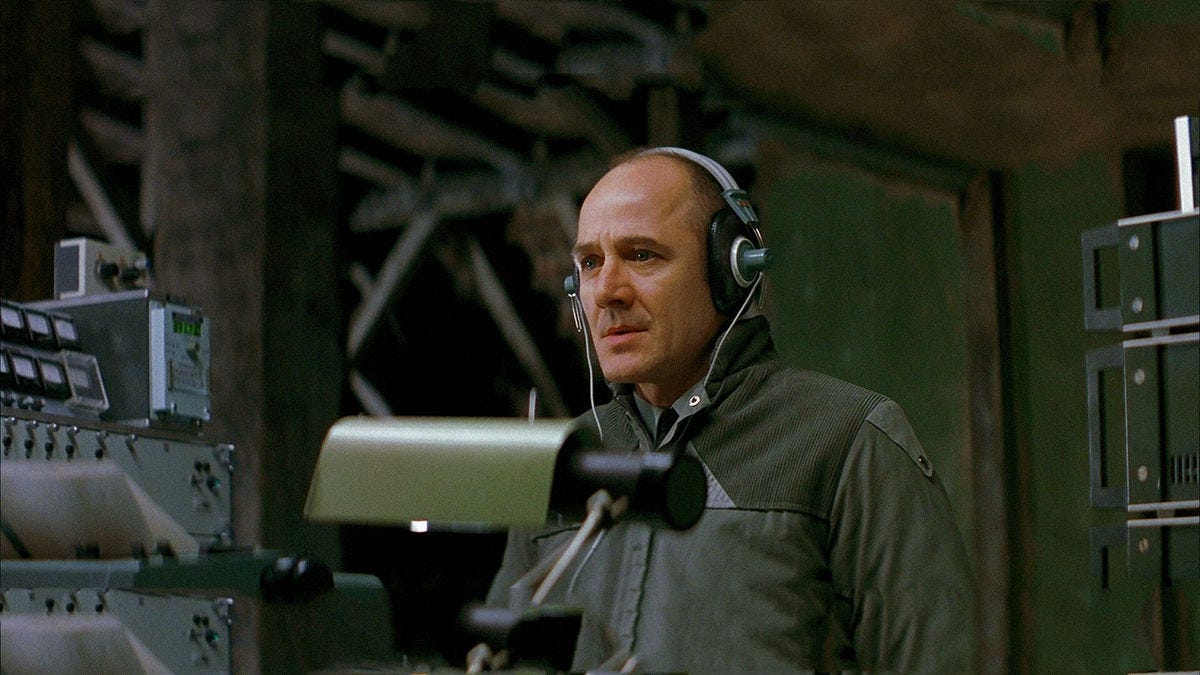

“The Lives of Others” tells the story of a Stasi secret police officer named Gerd Wiesler, dedicated to interrogating East Germans suspected of disloyalty. Wiesler likes being close to power. One night Weisler’s only friend, another Stasi agent, invites him to see a play by an East German playwright named Georg Dreyman.

Dreyman is considered loyal to the state. He only writes plays about the heroic proletariat, a pre-approved topic. Still, the Stasi Wiesler immediately suspects him and decides to surveil and wiretap the apartment the playwright shares with his actress girlfriend.

We don't know if Dreyman writes plays uncritical of the regime because he is a true believer, or because he doesn’t want to lose his job, but it’s necessary to understand that he’s no radical. He’s an everyman, in many ways caught up in the same systems of oppression as Weisler is. Dreyman thinks many things are wrong in the DDR, but he mostly keeps those thoughts to himself. He’s an inner émigré, not trying to flee to West Germany and get shot, or protest and get thrown into prison. He likes his comfortable apartment. His dissents are small and private. He reads banned books in his home and expresses concern for his friends persecuted by the government.

Nevertheless he’s more human, more alive than Wiesler is. Dreyman doesn’t just go to work and come home and numb out with state-run news like his Stasi spy counterpart. Instead, he enters into and affirms a shared physical reality with people around him. He tries to make his little world more beautiful.

We see Dreyman kicking the ball with kids playing in the street and joking around with them. We see him reading books, not just watching a screen in a stupor like Wiesler. We see him cooking real food, making love to his girlfriend, having parties with his fellow writers, dreaming up plays and listening to music. Distinctly human and life-affirming activities.

By contrast, Weisler’s own life is colorless and drab. He lives alone. He eats garbage. He lacks the joy, love, and belonging that Dreyman experiences as a person with a lover and friends and a creative outlet. Not only does Wiesler not know his neighbors, his neighbors actively fear him. A child tells him in the elevator, “My dad says you are a bad person who puts people in jail.” Weisler replies, “Oh really, what is his name?” When Weisler gets lonely he calls a prostitute who gives him only fifteen minutes. The two men live in the same town and under the same unjust laws, but their inner lives could not be more distinct.

While spying twelve hours a day on Dreyman, Weisler starts to care about him and his girlfriend even to feel protective of them.

Dreyman has a friend, a fellow playwright, who has been blacklisted. Dreyman tries to advocate for his friend with DDR officials but nothing comes of it. The friend now unable to work because he is insufficiently loyal to the government gives Dreyman a piece of sheet music. It is Beethoven’s “Sonata for A Good Man." Shortly thereafter Dreyman's blacklisted friend dies by suicide. Heartbroken, Dreyman sits down at the piano and begins to play.

We see Wiesler listening to Dreyman play the sonata over the wiretap. As he listens he starts to cry. It is paying attention, and taking in the beauty, that leads Weisler out of a head (which can justify and rationalize cruelty) and into his heart, which feels pity for his fellow man.

Dreyman becomes convinced that he must speak up about the conditions for ordinary people in East Germany. The spy who is supposed to report on him for “wrong think” begins to cover for him instead.

What do we do when our hearts have turned to dust? When we're spiraling? When it feels like everything is moving towards depravity and we feel powerless to do anything about it? When we just want to numb out and watch Netflix, or do drugs or disassociate?

Thankfully we do not live in East Berlin in 1984. We can vote and write letters and make calls.

Still, we do live in a markedly disembodied time. If you say, “I don’t like my life. I feel sad.” Many people will suggest that there is something wrong with your neurotransmitters. There is a pill for that. Of course, medication for depression and mental illness is sometimes necessary. It saves lives. But sometimes when you don’t like your life, you have to actually change it.

When I was spiraling five years ago during Covid about losing my job, and possibly my small business, and feeling like everyone on the Internet was shouting all the time, what got me out of it was learning to climb rocks outside with other people. I had no interest in learning to climb. I had never played a sport, and standing on dime-sized ledges high above the ground sounded like a bad idea. But I knew a climber who seemed enthusiastic, so I decided to do the opposite of what I would typically do and asked him to teach me.

Like Weisler, it was paying attention to something real and outside myself, it was being fully present that reconnected me with my heart, and helped me to figure out what to do next.

We think we know ourselves, but what if we don't know ourselves at all? Normalize holy agnosticism, open-heartedness, and trying something new. I thought I would hate climbing. I loved it. Weisler, the Stasi spy, thought he knew what he believed, but an encounter with another person, and with a piece of music, changed his mind.

Watch the movie and tell me what you think. And remember, you don’t have to do something big to change your own life or the lives of others.

Reading this and following along with some of the resources you posted on Instagram reminds me of the resources Rod Dreher has been pulling together but from a more right wing perspective. I'm wondering what it says about our moment that each side of the spectrum sees some of what you are talking about here.

When I wrote the book, this was 100 percent true of the Woke Left. Now we are starting to see the same thing manifest on the Woke Right. Don’t be deceived: a totalitarian spirit, and its concrete manifestation, could come from either side. It is not the case that only left-wing people are susceptible to it. All of us live in the kind of society and culture identified by Arendt in 1951 as vulnerable to the appeal of totalitarianism.

That's Dreher today continuing to extend these themes. What I find frustrating is the lack of people willing to look at excesses of both sides.